Introduction

Does family background affect children’s educational attainment? This is one of the most pressing questions in sociology. Many studies concentrate on how families’ social and economic wellbeing affect children’s school performance. For example, more educated parents may find it easier to help their children with algebra homework. In addition, it is easier for wealthy parents to afford high quality tutors for their children struggling in English. However, it isn’t just parents’ education and income that shape children’s school outcomes, but also children’s genes.

Past research has shown something very interesting and important. Genes seem to be more important for children’s school performance in well-educated and wealthy households, but less important for children with less educated parents with lower incomes. A common explanation is that the importance of genes depends on children’s environments. Whether they know it or not, higher educated and wealthy parents are tailoring children’s environments to their genetic potential, for example by hiring a tutor, buying a book that fits their child’s interests, or taking them to their favourite museum. Less educated parents with lower incomes may find it more difficult and lack the resources to create tailored environments that allow their children to realize their full genetic potential.

Tina and I noticed that something is missing from all of this. Children’s family environments are not just defined by their parents’ education and income, but also by the composition of their households. One of the most important dimensions of advantage or disadvantage during childhood is whether children experience a parental separation or not. Parental separation not only decreases the resources, such as income, available to parents and their children, but it is also simply a stressful event for everyone involved. So we began to wonder whether parental separation might have consequences for the importance of children’s genes for their educational outcomes.

In an open access study that Tina and I published in the Journal of Marriage and Family, we sought to answer two questions. First, does parental separation lower the heritability of children’s school performance? Second, are the differences in the heritability of children’s school performance attributable to differences in parental education and income?

First we need to define heritability. Heritability is a statistic, which expresses the proportion of individual differences that can be explained with genetic as opposed to environmental variation. Put simply, heritability tell us to what extent genes matter in relation to social influences. So if we say, for example, educational attainment is 100% heritable, then we’re saying that differences between children are accounted for completely by genes and that social influences don’t explain any differences. If we say educational attainment is 0% heritable, then we’re saying that differences are accounted for completely by social influences and that genes don’t explain any differences at all.

Parental Separation, Genes, and Children’s School Performance

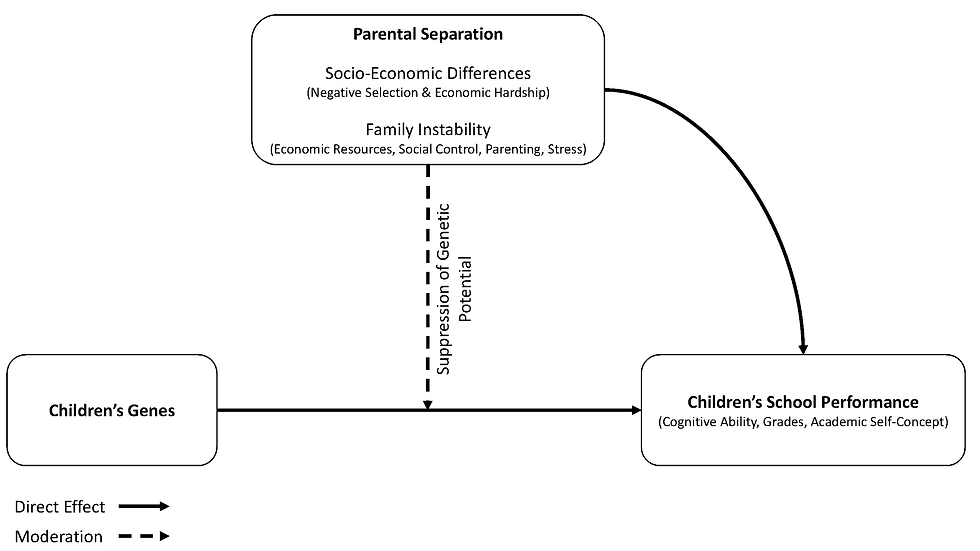

How parental separation and children’s genes interact to affect children’s school performance is a bit complicated, so Tina and I tried to depict this in Figure 1. What you see first is that genes affect children’s school performance, i.e. the horizontal line in Figure 1. We focus on three dimensions of school performance: cognitive ability, math grades, and children’s self-perceived ability in math. Genetic influences for indicators of school performance are well-established. For cognitive ability and academic motivation, genes account for about 40% of the total variation in childhood. Heritability estimations for school grades range from 34% to 70%.

Figure 1: Parental Separation as Moderator for Genetic Influences on Children’s School Performance.

It is important to remember that how genes affect school performance is not yet fully understood. However, it is widely acknowledged that a large number of genetic variants are involved. This means that there is not a single gene that affects children’s educational outcomes, but hundreds or even thousands. The heritability estimations for school performance simply provide insights about the role of genes and whether children can express their genetic potential related to education.

We also know that parental separation can negatively affect children’s school performance, i.e. the curvy line in Figure 1. However, there is quite a bit of debate on why or how parental separation affects school performance. Some scholars say that it is not parental separation that affects children negatively, but that less educated parents with lower incomes are simply more likely to separate. Therefore, it’s the lower levels of income and other social and economic resources that negatively affect children. Other scholars disagree and argue that there are parental separation has detrimental effects above and beyond losses in household income. For example, the stress of separation may change parents’ behaviours and parenting strategies as well as children’s perceptions of parenting practices. Moreover, it may be more difficult for a single parent compared to two parents to monitor and control their children’s activities, especially due to increased time constraints.

However, we think that parental separation may also suppress genetic influences on children’s school performance, i.e. the dotted vertical line. This is called a gene-environment interaction. Due to periods of economic hardship, separated parents may not be able to provide relevant goods or services, such as that new book, that further the development of children’s cognitive and non-cognitive skills. In addition, separated parents may spend less time with their children and are less able to respond to children’s needs or to monitor children’s homework and to organize enrichment activities, such as visiting museums. As a consequence, children lack tailored inputs that are adapted to their needs and in line with their genetic dispositions. Moreover, parental separation increases children’s exposure to stress, which can lower children’s chances for the realization of their genetic potential.

We therefore expect that genetic influences on children’s school performance will be higher in two-parent households compared to single-parent households generated by parental separation (H1). However, if the differential environments created by two-parent and single-parent families following separation are due solely to socioeconomic differences, then the heritability of school performance would not be higher in two-parent households compared to single-parent households once adjusted for parents’ socioeconomic status. However, if family instability processes following parental separation, such as a change in social control, parenting, and stress, suppress genetic influences on children’s school performance, then we expect genetic influences on children’s school performance will be higher in two-parent households compared to single-parent households generated by parental separation even when adjusted for parental education and household income (H2).

Data & Methods

In the next few paragraphs, we shortly describe how we answered our research questions and tested our expectations. If you have unwavering faith in us, feel free to skip to the results. If this isn’t enough information for you, the paper with all the details is open access. We used the first wave of the TwinLife study. TwinLife started in 2014 and provides a population-register based sample of identical twins and same-sex fraternal twins as well as their families residing in Germany.

We selected three different indicators for school performance: cognitive ability as the most important single input factor for education, math grades as an indicator for educational performance, and math academic self-concept as motivational measure. We measured children’s cognitive ability with the Culture Fair Intelligence Test (CFT 20-R). The CFT is a widely used standard psychometric test to indicate non-verbal intelligence. Math grades were retrieved from pictures of children’s most recent report card. Finally, we operationalized self-perceived ability using the following 3 questions on math academic self-concept, which were measured on a five point scale: 1) I am … in math (1 “not talented” to 5 “talented”); 2) I know … in math (1 “just a little” to 5 “a lot”); 3) In math, many things are… (1 “easy” to 5 “difficult”).

To test whether household composition affects the relative importance of genetic influences on cognitive ability we distinguish between children who live in two- and single-parent households. Children living with both biological parents, married or cohabiting, are categorized as living in two-parent households. Children in single-parent households are living with a mother who is either single, separated or divorced, or married but living permanently apart. We excluded step-families, single fathers, same-sex couples, widowers and single-parent families where the father never lived in the twin’s household. We used mothers’ education and household income to approximate differences in socioeconomic background.

We assessed the relative importance of genetic influences on children’s school performance by family structure using the Classical Twin Design (CTD). The CTD is widely used in behavioural genetics to estimate to what extent differences in individual characteristics can be explained with differences in genetic influences and differences in environmental influences. The CTD design identifies the relative importance of additive genetic influences, which is a known heritability estimate. The logic is: twins are born and raised at the same time. Identical twins are additionally genetically alike, whilst fraternal twins share on average about 50% of their DNA. If identical twins are on average more similar than fraternal twins, then that must be attributable to genes. The CTD builds upon these distinct features to decompose the total variance of an outcome into variance that can be attributed to additive genetic influences (A), shared environmental influences (C), and non-shared influences including measurement error (E). This method is labeled the ACE variance decomposition method.

Results

Figure 2 shows how the relative importance of genetic influences (A), shared environmental influences (C), and unique environmental influences (E) for cognitive ability, math grades and math academic self-concept for children living with one and two parents (unadjusted), and whether these results change once we adjust for mother’s education, and for household income.

Figure 2: ACE Variance Decompositions for Twins Cognitive Ability, Math Grade, and Math Academic Self-Concept by Parental Separation – Unadjusted, Adjusted for Mother’s Education, and Adjusted for Net Household Equivalent Income. Variance Components in Percent.

We found that genetic influences were larger in two- compared to one-parent families for all outcomes, although differences tend to be negligible for math grades. In one-parent families, genetic influences accounted for about a third of the total variation in cognitive ability (32%), nearly half of the total variation in two parent families (47% respectively). Differences are even more striking for academic self-concept. While less than one-fourth of the total variance in math academic self-concept is attributable to genes in one-parent families, half of math academic self-concept variance is accounted by for genes in two-parent families (23% and 50% respectively). Although the trend for math grades is similar to cognitive ability and academic self-concept, the differences we find by family structure tend to be negligible: 41% in one-parent families and 44% in two-parent families.

In the next step, we tested to what extent differences in the relative importance of genetic influences are associated with socioeconomic differences by adjusting the models for educational or financial differences. The results showed that mother’s education had a positive impact on children’s cognitive ability and math grades in both one- and two-parent families. However, mother’s education did not affect children’s math academic self-concept. For all three outcomes we found that household income had a positive impact in two-parent families.

For cognitive ability, we found that mother’s education explained about 13% of the total variance in one-parent families and only about 5% in two-parent families. Adjusting for mothers’ education reduced shared environmental influences and to a lesser extent genetic influences. In one-parent families shared environmental influences accounted for about 18% (unadjusted 27%) of the total variation, and genetic influences for roughly 27% (unadjusted 32%). In two-parent families, the relative importance of genetic influences remained nearly the same and explained about 46% of the total variation, while shared environmental influences decreased and accounted for about 10% (unadjusted 14%). If differences in mothers’ education were driving the differences in the heritability of cognitive skills between single- and two-parent households, then mothers’ education would have a explained a larger part of the total variance and reduced the relative importance of genetic influences to a stronger extent. However, the genetic influences remained almost stable after adjusting for mothers’ education and differences in mothers’ education therefore did not seem to account for the differential heritability of cognitive ability.

Household income explained less of the total variation in cognitive ability than mother’s education: only about 1% of the variation in cognitive skills in one-parent and about 3% in two-parent families. Consequently, we found no substantial changes in the relative importance of genetic and shared environmental influences compared to models without the adjustment for household income. In sum, adjusting for mother’s education and the financial situation of the household did not alter our base findings as substantial differences in the importance of genetic influences remained.

For math grades we found a less pronounced pattern as for cognitive ability. Adjusting for mother’s education explained about 7% of the total variance in math grades in one-parent families and 6% in two-parent families. Again, household income explained less of the total variance (about 2% in one-parent and 3% in two-parent families). Both the relative importance of genetic influences and shared environmental decreased somewhat once adjusted for mothers’ education in one-parent families, while only the relative importance of shared environmental influences was lowered in two-parent families. However, the differences continue to be negligible once controlled for household income.

Results for math academic self-concept showed that shared environmental and genetic influences remained almost unaffected when adjusted for mother’s education and household income. The unadjusted results that showed substantial differences in genetic influences on math academic self-concept by family composition remained after adjusting for socioeconomic differences: genetic influences were consistently about twice as large in one- compared to two-parent families.

Conclusion

Our findings for cognitive ability and academic self-concept support the notion that processes associated with parental separation, such as more distant parenting, reduced parental monitoring, and higher levels of stress among children, lowers the genetic influences of children’s school performance. Genetic influences accounted for substantially more variance in children’s school performance in two- compared to one-parent families. Further, the higher genetic influence in two- compared to one-parent families is not attributable solely to educational or income differences between households. Compared to the tailored environments of two-parent households, the environments of children in single-parent households seem less able to enhance children’s chances to realize their genetic potential.

Our study highlights promising avenues to facilitate a better understanding of heritability differences in children’s school performance by family structure. For example, further research is needed to examine whether the impact of parental separation differs by children’s age, because children’s vulnerability for negative life events may vary over their childhood. Children rely almost exclusively on familial resources during early childhood, whereas more non-familial contexts, such as schools, teachers or peers, become more influential as children grow older. In sum, to gain a better understanding on the link of parental separation and genetic influences, future research needs to study different outcomes, while accounting for the timing of parental separation as well as the duration of exposure to marital conflict.

In addition, future research should examine the diversity of single- and two-parent households in greater detail. For example, we were not able to include step-parent families in this study. However, research on family instability highlights that divorce is one of many transitions that may affect children negatively. Future research is needed, for example, to examine to what extent the presence of a step-parent changes the quality of the family environment. An additional adult in the household may be able to help facilitate a rearing environment tailored to the needs of children and thereby help children express their genetic potential. In contrast, stress and conflict associated with remarriage and merging two households may further suppress the realization of children’s innate abilities.

In addition, our findings refer to Germany, a welfare state that provides a relatively high level of social security. However, German labour market and family policy also actively incentivizes a male-breadwinner female-homemaker division of labour with low coverage of all-day childcare and schooling. Differences in the realization of children’s genetic potential by household composition may be larger in liberal societies, such as the United States, where women are at a considerably higher risk of poverty following divorce. Compared to social democratic states where social systems secure divorced women’s socioeconomic wellbeing and facilitate labour market participation, such as Sweden, differences in the heritability may be lower.

It is important to note that our study should not be used to argue for more restrictive divorce legislation or that divorce is “bad” and should be avoided at all costs. We do not know how the children who experienced a parental separation would have fared had their parents stayed together. Family environments characterized by marital conflict are likely not conducive to the realization of children’s genetic potential. Our study has implications for policies targeted at improving the educational disadvantages of children living in single-parent households. For example, tailored learning environments within and outside of schools targeted at children living in single-parent households could complement income transfers to ensure children’s chances for the realization of their genetic potential.

Commentaires